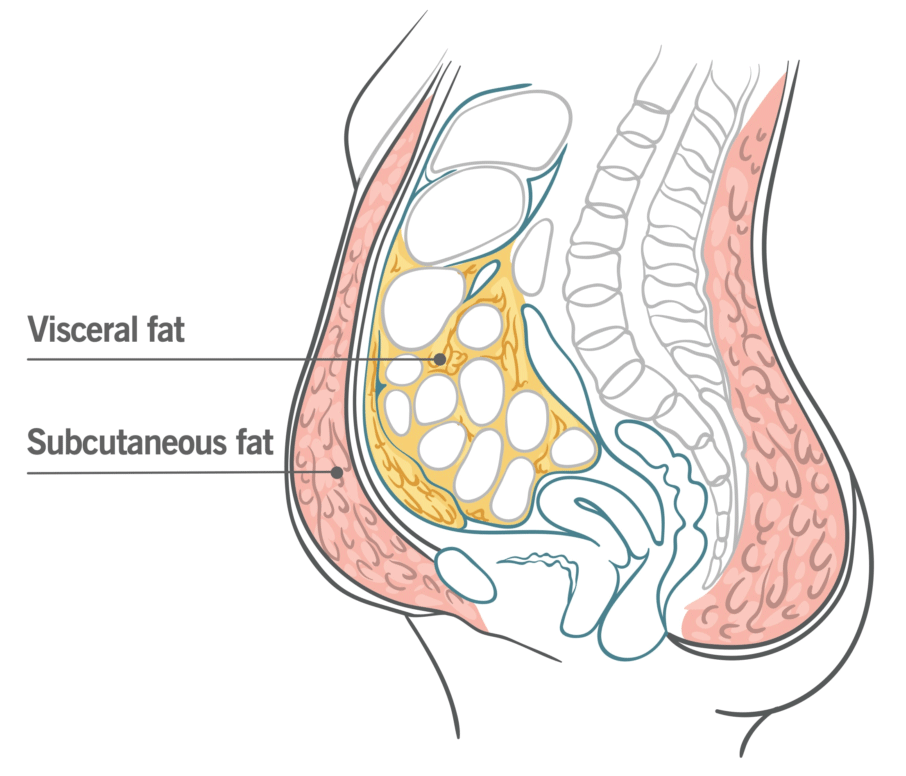

Research demonstrates that inadequate sleep when combined with unrestricted food access leads to higher calorie consumption and consequent fat accumulation – particularly unhealthy abdominal fat accumulation. According to this research study, inadequate sleep resulted in an increase of 9% total abdominal fat area and 11% visceral abdominal fat when compared to a control sleep group; visceral abdominal fat deposits deep within the abdomen surrounding organs which has strong associations with metabolic and cardiovascular diseases.

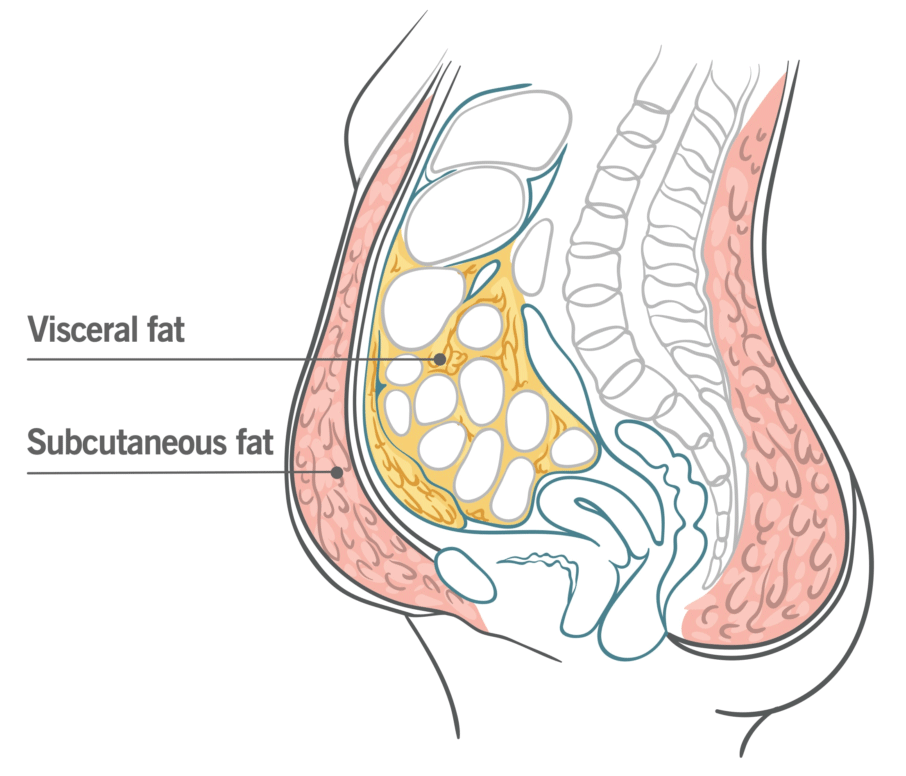

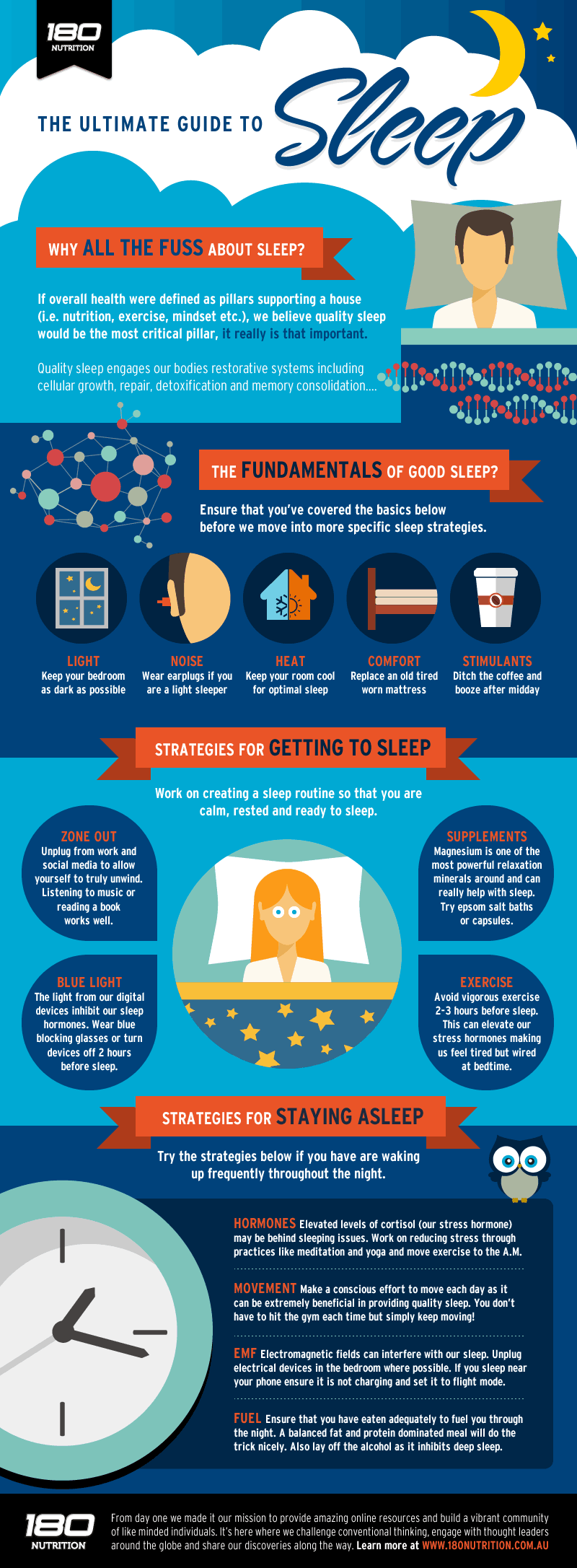

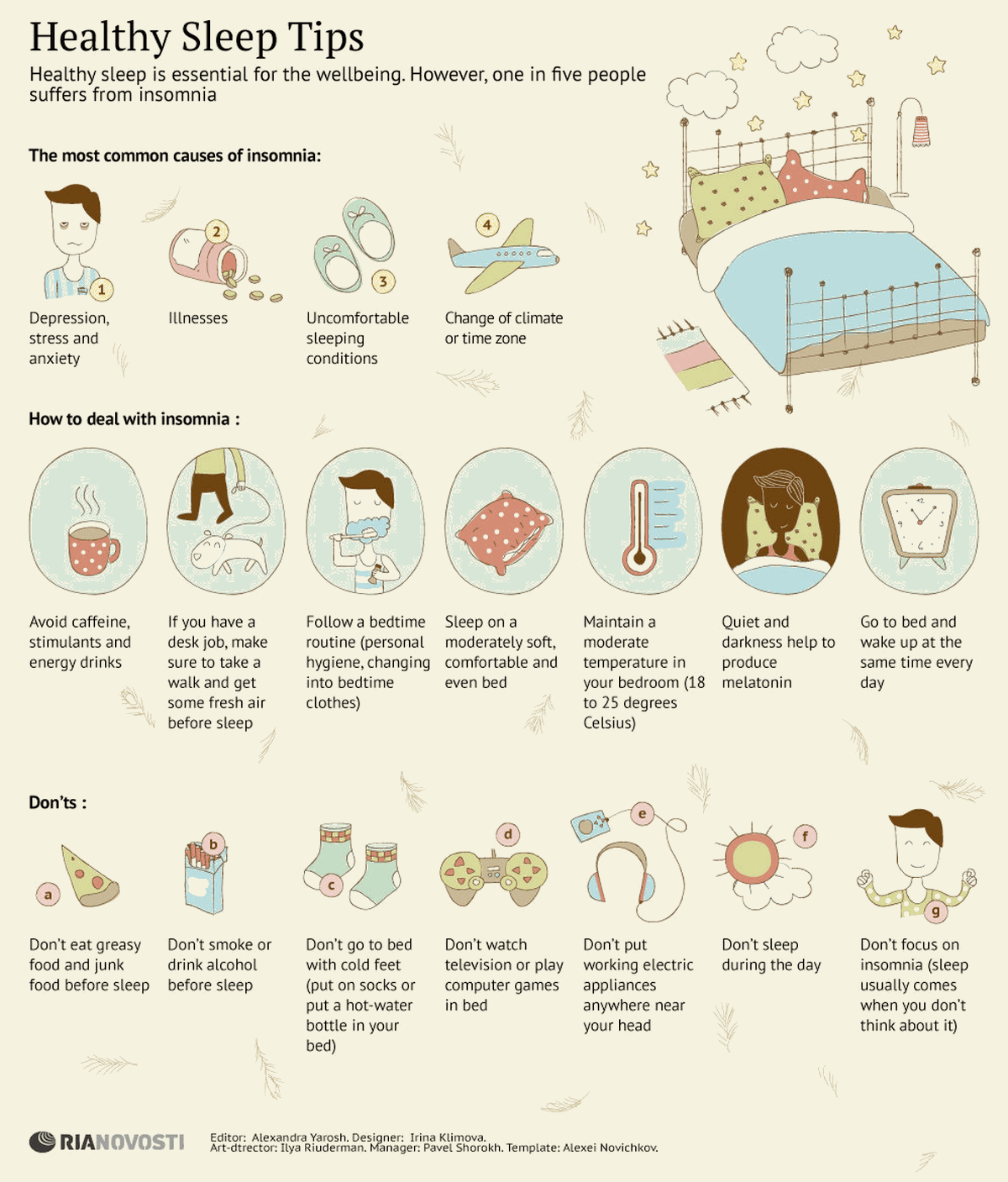

Sleep deprivation has become an increasingly common behavior choice, affecting more than one third of individuals in the US each night. Shift work and mobile device use at bedtime have contributed to inadequate rest, as have use of smart devices and social networks during usual sleep times. People also tend to consume more food when awake for longer hours without increasing physical activity levels.

These results demonstrate that shorter sleep, even among healthy and relatively lean young individuals, is linked to an increase in caloric intake, slight weight gain and significant increased accumulation of belly fat.

Fat tends to accumulate subcutaneously; however, lack of sleep appears to redirect it toward visceral fat storage areas – this may explain why even with reduced caloric intake and weight reduction during recovery sleep periods, visceral fat continued increasing.

Lack of sleep appears to be an under-recognized cause of visceral fat deposition and that short-term catch-up sleep won’t reverse its accumulation, providing evidence for long-term lack of rest contributing to obesity epidemic, metabolic, and cardiovascular diseases.

The study included 12 healthy obese-free participants. Each person participated in two 21-day sessions held in an inpatient environment over a 3-month washout period and were randomly allocated either to a normal sleep control group or restricted sleep group for one session and then switched the following session.

All groups were offered free food choice during the entire study, and appetite biomarkers; fat distribution (including visceral and subcutaneous fat); body composition; body weight; energy expenditure and consumption were measured and monitored throughout.

The initial four days were an acclimation phase in which all individuals were permitted 9 hours of sleep in bed per night; restricted sleep group participants received 4 hours per night while control group slept 9 hours for the remaining 2 weeks. Both groups then experienced three recovery days and nights with 9-hour nights for optimal recovery.

Sleep restriction duration was associated with over 300 additional daily calories consumed, including approximately 13% more protein and 17% more fat consumption compared to the acclimation stage. Consumption peaks during initial sleep deprivation days before levelling off in recovery mode until energy expenditure remained almost identical throughout.

Visceral fat accumulation was only detected through CT scanning; otherwise it would have gone undetected as weight gains were relatively minor, at only 1 pound. Weight measures alone would provide false assurance about health implications from lack of sleep; more worrying is the cumulative visceral fat increase over a prolonged period.